I’ve been reading a book by Carl Gold “Fighting Churn with Data”. I’m going to write a full review of the book later, but now I want to share some thoughts on a dataset construction for churn prediction. The problem is as follows: we want to create a dataset for churn prediction. We can measure multiple metrics for each user describing their activity at some period in the past ending at the moment of the measurement. Suppose that such metrics are measured on a daily basis, so an observation unit is a user-day pair. For target observations associated with churn, everything is clear: we need to describe a user’s activity right before churn or a few days before that. But what about the non-churn observations? Should we include each day of a user’s lifetime in the product before they churn? Apparently no. Then how to select the days? And what if users don’t churn at all within the whole dataset?

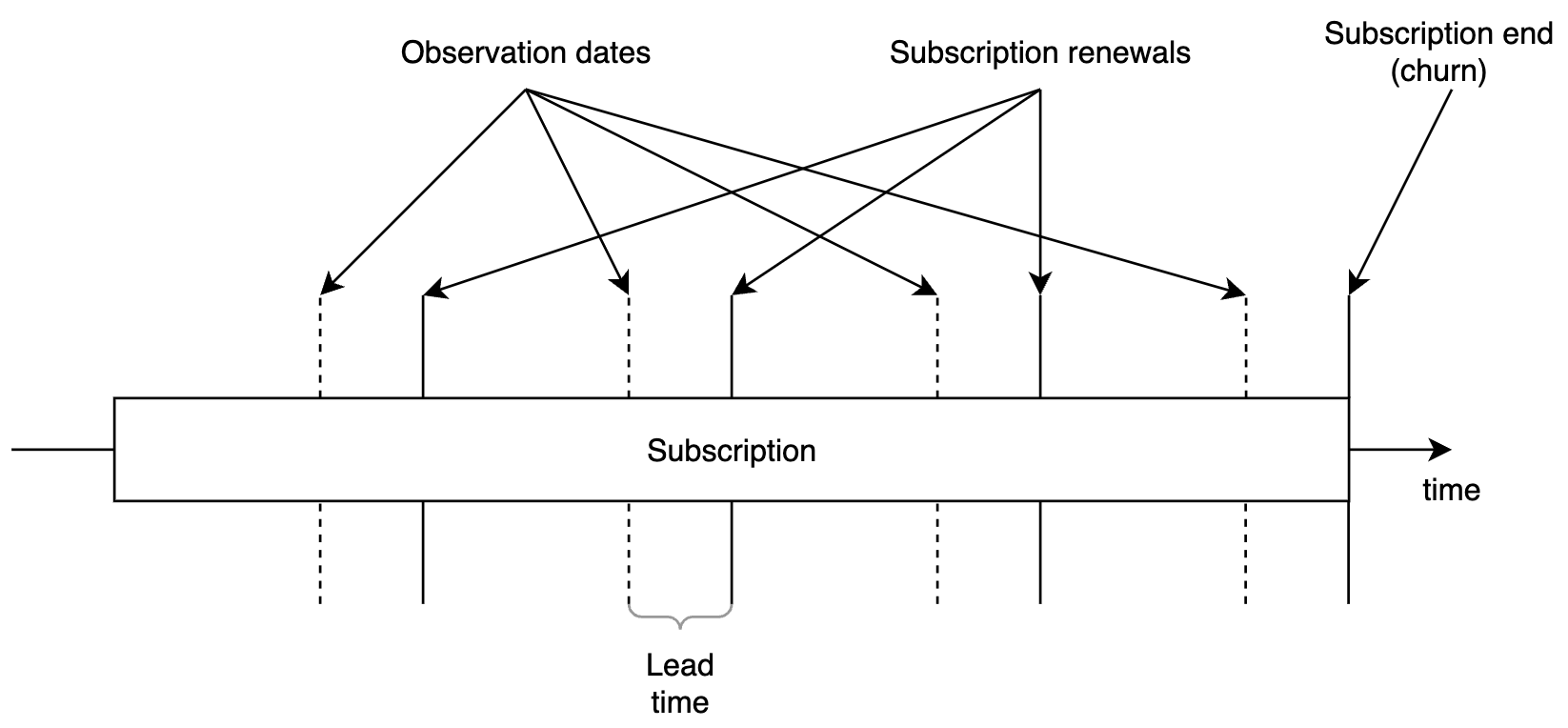

Let me first demonstrate the author’s approach to the problem. The approach is valid for subscription-based products where churn is associated with the end of the subscription period that user refuses to prolong. However, it might be easily extended for other types of products and churn definitions. The idea is based on an assumption that a user makes a decision whether to stay or leave each time the current subscription period comes to an end. It means that each subscription’s end is a potential churn event and it should be included in the dataset as an observation. In addition, it’s better to step back in time for a few days before this point because users tend to change their behavior before the actual churn event: for example, they drop their activity or they perform unusual actions like downloading a lot of content preparing to delete their account. The author refers to this shift as “lead time” (I’ll denote it as \(L\)). Below is an illustration of the observation periods idea.

And here’s what I find misleading in this concept. In general, there might be two purposes for building such a predictive model:

- Use it in production environment trying to retain the users who are about to churn (e.g. by offering them a discount).

- Analyze the model features’ importance in order to understand what makes users churn and improve the product towards user needs.

If we work with the first case, everything is fine. Indeed, each time before a subscription period ends we need to check whether the user is likely to leave and try to prevent their churn in case they are intending to do this according to the model’s point of view. In other words, {user_id, subscription_period_end - \(L\)} pairs form a dataset for the model.

But here’s a problem with the second case. Among the model’s features, it’s common to use the length of time a user has been using a product (it’s often called “age” or “lifetime” which is confusing so Carl Gold uses the term “tenure”). The trick is that the tenure distribution being measured when users churn is different compared to other observation dates. ML models usually see this signal clearly: roughly speaking, the higher the tenure is, the less likely the user is about to churn. This is what I see each time I build a churn prediction model.

Consider a metaphoric example. Suppose you’re a doctor from the 19th century when the child mortality rate was high. You want to predict whether a child will die or not. You know that the first months of life are crucial for children. So if you see a child of, say, 3 years old, you understand that this child has already passed the most dangerous period and, therefore, is likely to survive. Despite the fact that this feature has strong predictive power, it doesn’t help you to understand what makes children die.

Okay, what’s then? One of the possible solutions is to use a single observation for each user within a fixed observation period, e.g. first N days of their lifetime. This way, the tenure distribution for both churned and retained users is identical. This approach is valid but it also has a few drawbacks:

- We have to remove all the users who have already churned within N days. Why? Consider a user who left the product after their first day and suppose N=7. At day 7 the model captures that a user was active only 1 out of 7 possible days and infers that the user is likely to churn. So leaving such users in the dataset would facilitate the model to predict churn and wouldn’t bring us closer to understanding the churn reasons.

- The tenure feature becomes useless since its values are identical for all the users in the dataset.

- The fixed observation period captures only initial user-product interaction. It might be not enough for some complex products, especially in B2B area where users might need more time to understand the product.

Instead, I suggest using another strategy, similar to look-alike method. Again, for each user we consider only a single observation date. First, we select all the users who churned. Consider a churned user \(u\) who left when their tenure was \(t_u\). For such a user, we try to find a pair among the retained users at such a day when their tenure was \(t_u\). Thus, the dataset consists of pairs of users who have the same tenures but one of them churned while the other didn’t, so we can explore the differences in their behavior that lead to churn. The observation date for both paired users is \(t_u - L\).

However, such a straightforward pair selection is not enough in practice. Churned users are often less active (if active at all) before they churn compared to retained users. Hence, an indicator showing whether a user was active at \(t_u - L\) day is usually a powerful predictor but it doesn’t help to understand the churn reasons. Thus, besides demanding the same tenure, we could also require a retained user to be in the same state at \(t_u - L\) day as the churned user. The state might be defined in multiple ways and include any feature that would be a good predictor but sheds little light on the churn reasons. Coming back to the child mortality example, for a child who died at the age of, say, 6 months and who was about to die at the age of 5 months we would like to find a child who also was about to die at the same age of 5 months but survived.

There are a couple of nuances in this approach. First, a straightforward look-alike search has computational complexity of \(O(N^2)\) where \(N\) is the number of churned users, so for large datasets it might be slow, especially if the look-alike state includes many conditions. It might be facilitated by relaxing the look-alike requirements. For example, we might pick a retained user who was roughly but not equally as active as the corresponding churned user. Second, the described approach is valid when the number of churned users is less than the number of retained users. Otherwise, we should fix retained users and search for pairs among churned users.

I used this approach in multiple churn prediction projects and it worked well for me. Hope it will work for you too.